In this article, Alison Lenton, PhD, discusses the process of making a significant behavior change. Although changing any habitual behavior is difficult, understanding the process better can enable us to put ‘setbacks’ and ‘stagnation’ into context and see them for what they are: not failures, but an integral part of making any significant change.

Faunalytics’ 2014 Study of Current and Former Vegetarians and Vegans asked a mostly-representative U.S. sample of people age 16+ to report on their current and former eating habits and their attitudes toward meat and dairy consumption. Of the nearly 11,400 people who participated, approximately 12% were either former or current vegetarians or vegans. For the purposes of this blog, some of the study’s key findings were:

- The current failure rate of remaining a lifelong vegetarian/vegan (veg•n) in the United States is 84%. In other words, 84% of participants who had previously attempted a veg•n diet reported eventually giving it up.

- By the time the survey took place, approximately one-third of those who attempted to become veg•n lapsed within 3 months, and over half (53%) gave up within 1 year. And there were some (12%) who gave up even after having been veg•n for 6 or more years!

- Approximately 30% of “failed” veg•ns had also experienced previous failures. That is, nearly one-third had failed more than once to become veg•n. Nevertheless, 37% said that they want to try veg•ism again.

Given these results, it would appear that it is fairly difficult to transition from being omnivorous to veg•n, but any big change in habitual behavior can be difficult. Let’s look at why that is.

The behavior change process

Successful adoption of a new habit depends on the following (for a more complete summary, see this document from Faunalytics):

- Motivation, intention, and planning—you have to want the new behavior, you have to intend to undertake it, and you have to make plans to achieve it as well as plans for surmounting the inevitable obstacles

- Know-how—you have to understand how to enact the new behavior—and belief—you have to believe that you can do it

- Resources—e.g., adequate emotional, physical, cognitive resources in both the immediate and longer-term choice environments

- Positive reinforcement and absence of punishment—you have to perceive that the new behavior yields additional benefits and fewer costs

- Social and environmental support—do your friends/family understand or do they sabotage and challenge? does the environment provide you adequate opportunity and resources to enact the new behavior?

- Self-regulation abilities—are you any good at controlling your momentary desires/impulses? are you any good at directing yourself toward longer-term goals?

- Practice—repetition makes challenging behaviors easier and is key to their becoming automatic, which is when the behavior no longer requires conscious intention/thought

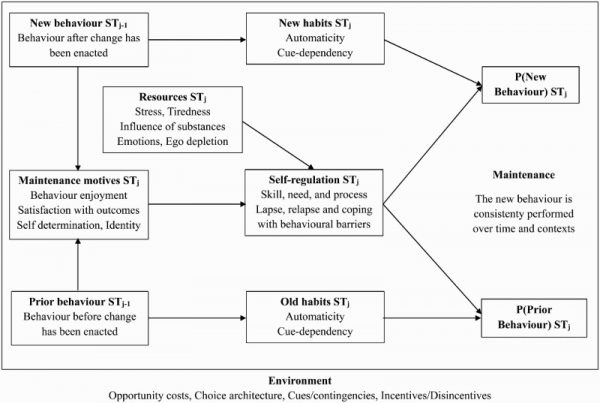

Add to this that the new and old habits then compete with one another for dominance. That is, for an old behavior to be replaced by a new behavior, the right internal (intra-person) and external (environmental) circumstances have to be in place. To illustrate, consider the following recent model of behavior change (Kwasnicka, Dombrowski, White, & Sniehotta, 2016):

According to this model, even after an initial change in behavior, the old and new ‘habits’ remain in conflict with one another. This is because the probability of one or the other habit dominating at a given point in time and in a particular situation depends on competition between the two habits’ different motivations, the distinct emotional resources required to enact or suppress them, the particular levels of self-control they demand, and just how automatic the associated behavior is (or has become). As the model points out, the new behavior may ultimately win out if it is practiced again and again, across different situations and over time.

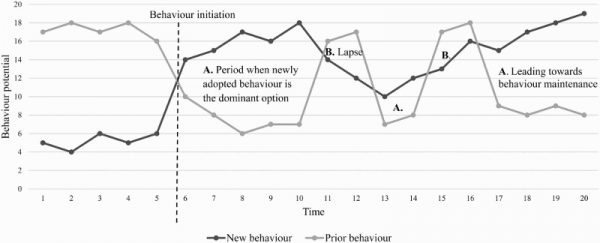

As a result, when one initiates a change in behavior, it is not uncommon to find that the old behavior continues to pop up now and again, at least until the new behavior becomes automatic; as illustrated by the figure below (also from Kwasnicka, Dombrowski, White, & Sniehotta, 2016).

And even then, it isn’t as if the old behavior and all of its triggers are completely erased. Think of it like how computers write files onto the hard drive: Writing a new file does not necessarily overwrite the old one. Remnants of the old file continue to persist and can be brought back into competition with the new file given the right (or, perhaps, wrong) circumstances. So even with everything in place, there will be setbacks: It takes time for a new habit to dominate the old one.

The fact that so many former veg•ns ‘failed’ but tried again—and want to try yet again—may actually be part of the process of becoming veg•n. Indeed, the 2014 Faunalytics Study found that the ‘failed’ veg•ns were more likely to indicate that they transitioned to their new diet over a matter of days/weeks, whereas for the ‘successful’ veg•ns, it was reported to be a lengthier process. In other words, it may be that the ‘failed’ veg•ns in Faunalytics’ study are simply at an earlier stage in their path to veg•nism, and many will still ‘get there’ in the end.

The findings also hint that any attempt at becoming veg•n may be successful to some extent: Those who ‘failed’ the strict test of maintaining veg•nism still reported eating less beef and pork thereafter than those who never tried to be veg•n (though we note that these data are correlational and, thus, causal conclusions are tenuous).

Overall, we suggest that taking a longer view of the process of becoming veg•n is both a theoretically and empirically valid one: For most people, becoming veg•n isn’t like a light switch that is flicked on at full brightness and never again flicked off. The process of becoming veg•n is more like a dimmer switch: Change is incremental and can sometimes move backward. Perhaps, however, once the dimmer is ‘on’ at all, there is at least a glimmer of light.

With that in mind, we recommend that animal rights and welfare organizations focus on informing people that becoming veg•n is a process made up of a series of smaller, achievable steps. This is because goals that are perceived to be feasible are more likely to be set in the first place than are goals deemed too daunting. These organizations should also give people explicit advice as to how to take those initial steps (e.g., simple rules-of-thumb such as “always choose the tofu option” and “when offered cheese, say ‘hold it please!’”), as research indicates that those with concrete if-then plans—especially plans that include strategies for managing potential obstacles—are more likely to achieve their goals.

At the same time, advocates should continue to advance the general message that these small steps lead somewhere: Veg•nism reduces animal suffering and death, not to mention that it improves human health and the welfare of our planet. To the extent that we can make the process of becoming veg•n seem more manageable to people, and get people to understand that it is indeed a process that includes stagnation and setbacks, then we expect that more people will set upon and, ultimately, stay on the path toward veg•nism.

This blog is a variation and extension of one Dr. Lenton wrote previously for Faunalytics.

I’d love to be able to click these images and see bigger versions- is there anyway to make that possible on this post? thanks!

It seems to me that this report may also point to the great benefits of advocating for meat/egg/dairy reduction as opposed to full veganism. More people will be receptive to this message. Thereafter, those people will become more receptive to the message of veganism because its now a smaller incremental change from where they currently stand. My two cents!

I like the decomposition of how behaviors are changed! I’ll be thinking about this model a lot in future situations.